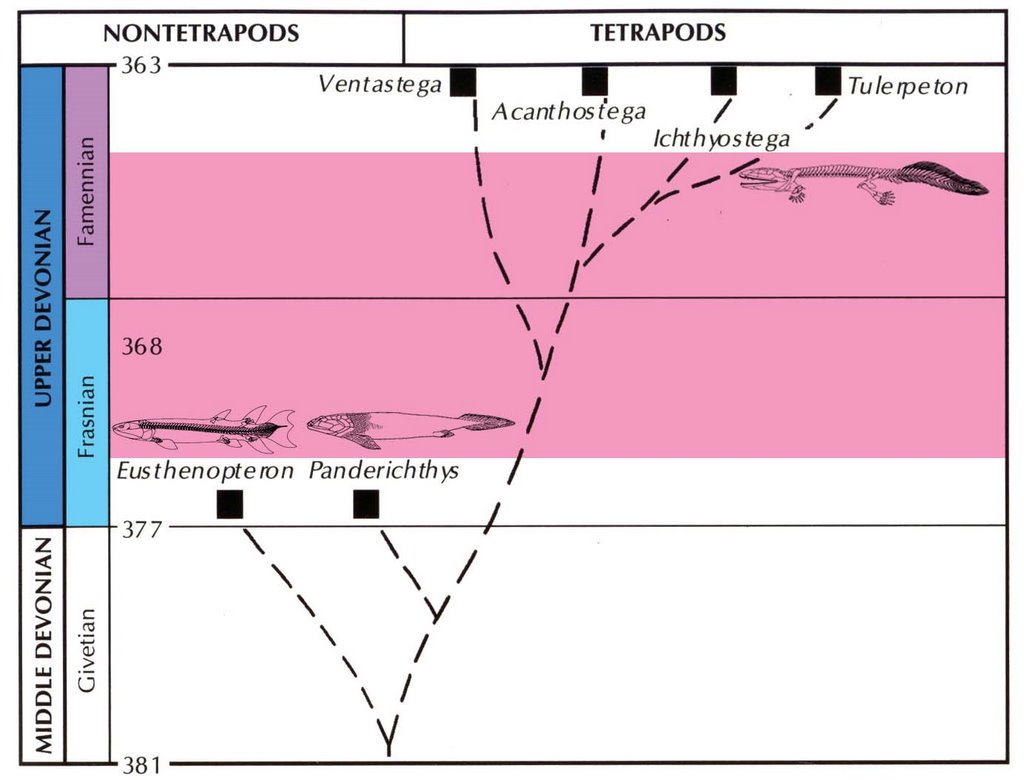

Yesterday, this picture got a lot more complicated. With the publication of tetrapod footprints some 18 million years in advance of this gap by Niedźwiedzki et al., the nice congruence between the node order of the tree and stratigraphy no longer appears so nice.

Here's a picture of the trackways (click for the full view):

[More below the fold]

This news has already broken, and I'm usually the last person to blog about it these days. Naturally, Ed Young has a good take on it. As noted by Jenny Clack in Ed's piece, the individual footprints are more convincing than the trackways in terms of their identity. Here's one from the supplementary information file (which is free to access).

[Picture deleted: I made a mistake, reading too fast and posted an image of Triassic temnospondyl footprints! A better image is this digital surface rendering from the main paper posted below]

But how "bad" is the record now that we know this? Well, bear in mind that lungfishes and tetrapods are considered (at least by the phylogenies in question) to be sister groups. That is, they split from their last common ancestor at exactly the same time. The earliest 'true' lungfishes (i.e. lungfishes with toothplates, and upper jaws fused to the braincase, etc.) are Emsian in age, roughly the same age as these new footprints. Recognizable close relatives of lungfishes, such as Diabolepis, Youngolepis and Powichthys, however, are considerably older. Do, we can set a minimum age for the origin of the tetrapod stem lineage down in very earliest part of the Devonian even if we do not have the fossils.

So, not surprisingly, the record is pretty bad. It's certainly 'gappy'. But we should not be too surprised that tetrapods emerged long before the time when we find their first actual fossils.